A drone flies through the air capturing data from a construction project. A directional drilling system that looks like a large version of the “Transformer” toy is helping contractors make and break joints for pipes. A compressed air canon is launching nails on a job site. A machine is doing what humans usually do: create sandbags.

More low-key: A seal around a tailgate isn’t permitting liquid material to seep through. An excavator hook is being used to avoid typical D-ring wear and tear.

Some equipment is rarely seen on a job site, because it is so unusual. Be it unusual or unassuming, such equipment exists because a contractor had a need for something that could not be found on the market and is helping grading and excavation contractors save time and money.

Kespry builds aerial drones or UAV (unmanned aerial vehicles) called Kespry Automated Drone Systems and an aerial intelligence platform, Kespry Cloud, for many sectors, including construction. In recent months, drones have been making their debut on such projects as asphalt production and road paving, used to track job progress and conduct site surveys.

It takes less than 20 minutes to fly a 60-acre site, and less than a minute to track progress. Each three-dimensional (3D) model contains millions of data points.

Kespry’s drone system collects high-resolution still imagery and processes it into highly comprehensive high-resolution, two-dimensional (2D) and 3D models of sites, including elevation and contour lines.

The sites can be comprised of any type of geography, including a construction project, a segment of terrain, a quarry, a pit mine, or a road surface, notes Garrett Smith, business development executive.

The high-definition images and maps enable drone operators to identify and label construction assets such as materials, equipment, temporary roads and structures. The automatic calculation of stockpile volumes enables construction crews to complete planning on site and earmark space for new assets and resources.

Case in point: In a road project, ongoing drone missions assist in surveying and planning by capturing the exact location and volume of the movement and excavation of land and materials, enabling those involved in its construction to identify areas that may cause delays or additional costs. “It can be incredibly beneficial for project managers to get a broad overview of their sites, but they derive a lot of value from executing really refined measurements across the site in a number of different ways,” points out Smith, adding that the system is “quite adept at providing a distanced surface area and volumetric measurements across the site.”

For use on construction sites, the drone is viewed as a replacement for manned aircraft such as helicopters or airplanes that fly over sites to take pictures, and in so doing are safer and cost-efficient, he says. “There are technologies out there that leverage the same data that’s collected from manned aircraft that can still generate pretty good 3D or 2D models of these areas, but the cost associated with flying manned aircraft, from the fuel to the aircraft itself to the pilot’s labor hours. Those costs are not a part of a drone’s mode of operations.”

As for safety, “it’s always safer to have a machine go in and do the work rather than a human in high-risk operations such as ascending a large tower for an aerial view or getting on top of a roof,” adds Smith.

And, as with any major equipment investment, there’s always the concern of the return on investment (ROI), and how quickly it can be derived.

Pointing out that ROI varies according to specific uses, Smith says those using a drone on a typical excavation or earthworks project would typically spend 20 to 22% less than they would have been using other methods. “They are executing their work at a much higher frequency—two or more times the frequency that they would have been getting previously potentially by manned aircraft or by other equipment used on the site—and they are spending four times less overall across their operations,” he says.

The Kespry drone is offered as a purchased in-house tool and is not available for rental, notes Smith.

In terms of time invested in training, the drone operates in an autonomous fashion “in that an operator would take it out to a site, set it on the ground, turn it on, and, using the mission planning tablet interface, would draw a box around the area on the map he or she wants the drone to capture data from, and hit ‘fly’,” says Smith. “The drone flies itself up to mission altitude, collects all of that data, comes back, and transmits the data to the tablet and to the website.”

As such, it does not require the depth of training necessarily for a traditional drone or a manned aircraft, says Smith, adding that comprehensive training can be done remotely and accomplished in the span of a morning or afternoon.

Kespry also provides a dedicated “customer success person” for specific construction accounts for site managers or project managers for continued training, updating, troubleshooting, and other needed support.

The Sandbagger Model II at work

The data in The Cloud enables it to be instantly sharable within an organization. Kespry provides data security and privacy, but within an organization, the data can be shared with whoever is authorized to view it, such as project managers, supervisors, subcontractors, the CFO, and other decision-makers who can derive benefits from the data, says Smith.

One of the issues currently on the radar regarding drone use is the regulatory space, notes Smith. “In the early days, we recognized there were some regulatory hurdles we needed to help our customers with, one being that customers in commercial operations needed to be exempt through the Federal Aviation Administration [FAA] 333 exemption process and to receive a certificate of authorization specific for their area of operations,” says Smith, adding that Kespry has a program to assist in the process.

The company also has been active in the UAV lobbying effort. That includes a successful effort to update regulations, which “drastically reduces the burden on commercial operators for safe and legal employment of drones in applications like construction,” he says.

The Sandbagger Model II filling system

Smith notes that there are “very broad applications for the technology that extend well beyond a daily surveillance or imaging of a construction site.”

The value of data collected as the use of drones on construction sites increases will leverage the ability in creative ways to enlarge their benefits, he adds.

“Another aspect of this is an R&D roadmap item that is likely of interest for construction users and is leveraging onboard computer vision and machine learning to do tasks, such as asset tracking across the site so that users will have updated where all of the personnel and equipment are across the site,” says Smith. “This enhances the safety; increases efficiency; and improves the logistics aspect of any larger, complex project.”

Smith notes that infrastructure is one area that has an “incredible volume of need” with the use of drones for infrastructure inspection likely to become an increasingly serious matter in the future. “There are tens of thousands of bridges and dams installed across the United States, and state and municipal agencies are on the hook for providing safety inspections and maintenance inspections over an annual period.”

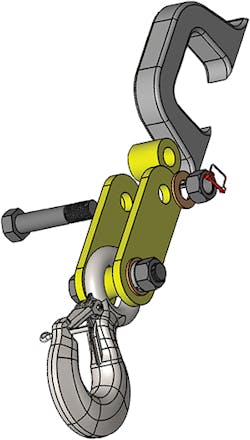

The Excavation Hook Clevis

A March 2016 survey by the American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) found that 33 state departments of transportation have or are exploring, researching or testing drones to inspect bridges, among other tasks.

The crews of MAXX HDD, a relatively new Houston-based directional drilling company for pipeline construction, have had a full plate of work lined up doing underground installation for roads, creeks, rivers, highways, cultural areas, and wetlands. While that is music to the ears of anyone in the industry, the company’s president, Travis Vander Wert, is concerned that deadlines are met in the safest and most efficient way.

The company had been using traditional directional drilling approaches, but in April, Vander Wert decided to try something different. “We were on a 3,000-foot drill on a wetland near Ardmore, Oklahoma,” he explains. “The exit side was really tight. We needed to make and break our drill string on several different occasions throughout the construction process.”

Vander Wert decided to use the Tonghand, which is designed to allow contractors to safely and efficiently make, break, and move pipe and handle drill pipe joints on the job site with one operator who can perform all functions from within the excavator cab. It can be attached to any brand of a 30- to 36-metric ton excavator.

Jason LaValley, founder and president of LaValley Industries, once worked in the horizontal drilling industry and sought a way to mitigate the dangers he saw in the traditional approach: the distance between employees radioing each other with directions and the inherent risks in the process of threading and unthreading pipes.

The PHIL Autogate Tailgate with Fluidic Seals

He created Tonghand as an exit side solution for the horizontal drilling industry. Tonghand is based on TongVise technology designed to make and break joints up to 120,000 foot-pounds of torque. Its control system and in-cab monitor allows contractors to torque pipe joints to a specified torque value.

Its gull wing design enables contractors to move roller arms out of the way to easily make and break reamers up to 60 inches and also work with sub connectors and rotate pipe strings. Roller arms and a shift function enable operators to thread and un-thread all drill pipe connections. Tonghand works with drill pipe connections ranging from 6.5 to 10 inches OD.

Vander Wert introduced the Tonghand on the wetland job. “The job site was tight, and it’s obviously a lot safer and more efficient method than what we had been using in the past, he says. “Those are two of the biggest things we consider when we look at things we can do to improve our company and it culture.”

Additionally, the client, the owner of a gas company, had seen the Tonghand at work and favored its use over more traditional methods, Vander Wert says.

Vander Wert finds the Tonghand to be user-friendly. A LaValley Industries onsite specialist, Craig Larson, stayed on the company’s work site for nearly two weeks to get crews trained and certified on its operation, he says.

Sometimes, unusual products emerge at the request of a contractor who cannot find the solution on the market. Such is the case when Caldwell Lifting Solutions was approached by a contractor who didn’t like using a shackle and a hook on his excavator because of the potential for the damage to the D ring and in being too loose of a fitting, thus swinging around, notes Dan Mongan, product development specialist.

The company designed the Excavation Hook Clevis. It’s manufactured out of alloy steel and is designed to be lightweight, yet rugged and easily installed and removed. Some components are powder coated, and other components are plated. It also has a hardened steel bushing where it contacts the D ring, specifically designed to reduce or eliminate wear on the D ring, says Mongan.

It is attached by removing a pin, loosening a nut, and pulling the bolt out of a bushing. It is designed to keep the hook oriented in the same direction all of the time so as to make it easy to attach the rigging.

A tool that was originally developed by the British military to launch chemical weapons is being used on some construction sites, notes Colby Barrett, president of GeoStabilization International.

The company’s Soil Nail Launcher is a compressed air cannon that can accelerate a 1.5-inch-diameter (38 mm), 20-foot-long (6.5 m) steel or fiberglass tube to 250 miles per hour (400 kph) in a single shot, according to the company’s website. It is designed to offer a number of benefits in contrast to conventional nailing techniques.

As the high-speed projectiles enter the earth, they generate a shock wave, causing the soil particles to elastically deform or “jump away” from the nail tip.

The bars enter the earth without substantial abrasion or loss of exterior corrosion protection. Soil particles collapse onto the bar in a somewhat undisturbed state, yielding pullout capacities designed to be up to 10 times that of driven or vibrated rods or tubes. Launched Soil Nails increase soil density in the nailed area.

Launched Soil Nails also can be perforated to allow for horizontal drainage and pore water pressure relief. It is designed to provide continuous axial capacity and drainage with the same element.

The perforated nails can be pressure-grouted with a variety of materials to increase bond capacity and soil properties throughout the nailed area. An epoxy-coated inner bar can then be installed inside the tube to construct a corrosion-resistant launched SuperNail.

While typically mounted on a modified tracked excavator, the Soil Nail Launcher also can be mounted on vehicles, long-reach excavators or crane basket frames. It weighs two tons and is designed to be portable enough to reach remote locations. The launcher unit has full articulation, enabling it to work around overhead wires, underground utilities, and guard rails.

Sometimes on a construction site, it’s not the equipment that’s unusual, but the job. In that case, equipment sometimes has to be custom-made to fit the job.

Josh Swank, vice president of sales and marketing for Philippi-Hagenbuch, says that while most of what his company has to offer is on articulated haul trucks for earth work, “we have custom-built equipment for a lot of weird applications. We’ve done them for hauling chicken slurry and for hauling wood waste after Hurricane Katrina after New Orleans.”

For those unusual jobs that may emerge, Philippi-Hagenbuch has designed the PHIL Autogate Tailgate with Fluidic Seals.

“Sometimes large trucks have to transport liquid waste like pulp slurry or chicken slurry or wet materials over public roads, and when they do that, they have to contain the material to make sure it doesn’t slop out and they’re not just dropping this liquid waste onto the public road,” notes Swank.

The company designed a rubberized seal for the back of a truck with a tailgate to mitigate the challenge of separate components such as the front suspension, front axle, hoist mechanism, and steering equipment without a tailgate having the potential to be overburdened.

In an effort to prevent spillage, operators may pile the load forward in the truck bed, which can cause damage to the canopies, overload to the front tires, and side spillage.

Tailgates act to close the rear of the truck and provide a larger loading target for more even load distribution from the front to the rear of the truck. A closed truck bed also provides a volumetric capacity increase of up to 20%, depending on the hauled material.

The potential for spillage over the sides or rear when a non-tailgated truck shifts gears on an incline or turns a corner is eliminated and tire damage is mitigated. There are no locks, cylinders, or controls—the Autogate Tailgate opens when the body dumps.

“We have equipment hauling radioactive waste in the West, equipment handling oil sands, gold, copper, iron ore, coal, and aggregate,” notes Swank. “We had someone from a salt harvesting operation who just showed up at our door a few years ago from the Yucatan peninsula in Mexico. They needed us to design a unique bottom dump trailer that wouldn’t corrode from the acidic nature of the salt.”

While contractors ask the company to provide purpose-built equipment for a particular job, in most cases, it can be repurposed for other uses, says Swank. While the average time for custom-built equipment is three months, some can be constructed in as little as four weeks, he adds.

Sandbags are often needed on construction sites to mitigate flooding and for water control, hazardous containment, soil erosion, fire control, roadway construction, and barricades.

Creating sandbags by hand can consume a significant amount of time, increase labor costs and can take a toll on an employee’s back, notes Paula Eaves, director of dealer development for The Sandbagger.

The Sandbagger has designed a machine that will fill the bags in a “fraction of the time” and mitigate the other challenges, Eaves adds.

The Sandbagger Model II with motorized auger is an automated sandbag-filling system used to fill four sandbags simultaneously, with four people to fill sandbags and one person to operate the front-end loader to keep the two cubic-yard hopper full. With unskilled labor, the unit is designed to fill at least 1,600 bags per hour with materials such as sand, soil, gravel, and mulch and other material less than 2 inches in diameter.

This Sandbagger system includes a sandbag filling machine with four stations, a safety grid, a safety shield, a hydraulic driven bidirectional auger and agitator to keep wet materials flowing, a gas engine, and a hydraulic motor. It is designed to be lightweight and truck-portable, with an optional towing package.

Ever since he started his company 15 years ago, Dane Willman, CEO of 3W Enterprises in Carpentersville, IL, has used the Sandbagger system in his company’s services, which focuses on visiting construction job sites to provide sand bags or fill them onsite.

“It depends on how many bags they need and what they need them for,” he says. “Someone who only needs 1,000 bags, we can throw it on a semi-truck and take them there. But if somebody needs 100,000 bags, then it makes more sense for us to go out and do it there. The freight costs are a factor because sand bags are so heavy.”

Using the Sandbagger system, Willman’s crews make the sand bags onsite with scales underneath the operation, so everything is made to order.

Most of the time the sand bags are buried after use or during use, he says. Some clients want the sand bags under a pipe to hold it up; others will place it on top of the pipe to hold it down.

“You’d think a sandbag is a sandbag is a sandbag, but it’s really not,” points out Willman. “We stock 80 different varieties of sandbags. Every one of our customers wants something a little different. They may want a different color, a different density of a bag, different fill material, or different weight.

“We specialize in doing this because nobody wants to fill sandbags,” he adds. “When I started my company, there were three people in the nation who did what I did. Now there are probably over 100. Every year I have to change my system a little bit to make my company better than anybody else.”

Willman says he’s tried other machines, but finds the Sandbagger to give a better output. He said he would like to see the system be able to weigh the bags without his crews having to place scales underneath the system.

Willman finds the Sandbagger easy to repair. “I’ve rebuilt these machines many times because parts wear and break,” he explains. “Parts become obsolete. We’ve worked with Sandbagger over the years. We felt the auger was too thin, breaking too often. They re-engineered the auger to make it thicker steel and tempering it, and now it lasts longer.”